We’re all a bit worried about the spread of illness these days, so where should we look for the most accurate, reliable, and up-to-date information? While Google can be a useful tool, relying too heavily on the web for health info is risky—how do you know if the information you’re getting is reliable? Which sources might be spreading “fake news”? How can we tell the difference?

More than half of students who responded to a Student Health 101 survey said they question the reliability of a health information source at least twice a week. Here’s how to know what to look for in a health website and recognize red flags so you can sort the best from the bogus.

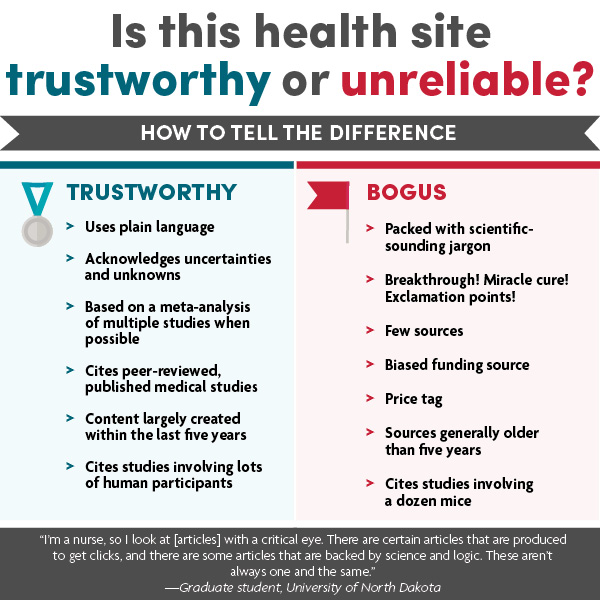

Trustworthy

- Uses plain language

- Acknowledges uncertainties and unknowns

- Based on a meta-analysis of multiple studies when possible

- Cites peer-reviewed, published medical studies

- Content largely created within the last five years

- Cites studies involving lots of human participants

Bogus

- Packed with scientific-sounding jargon

- Breakthrough! Miracle cure! Exclamation points!

- Few sources

- Biased funding source

- Sources generally older than five years

- Cites studies involving a dozen mice

“I’m a nurse, so I look at [articles] with a critical eye. There are certain articles that are produced to get clicks, and there are some articles that are backed by science and logic. These aren’t always one and the same.”

—Graduate student, University of North Dakota

What to look for

Trustworthy language isn’t overly technical. But it shouldn’t be “dumbed down” to the point where it isn’t accurate anymore, says Dr. Niket Sonpal, associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency at Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in New York.

Example

“According to the findings, eating nuts on a regular basis strengthens brainwave frequencies associated with cognition, healing, learning, memory, and other key brain functions. In other words, they help boost your brain power.”

Red flag: Scientific-y jargon

Red flag: Scientific-y jargon

You don’t want the terms to be so technical that you can’t understand them—if you can’t understand what it’s saying, or if it sounds like your kid sister is playing doctor, look for another resource.

Student voice

“My professors have told me that it should be explained as if you were explaining it to your grandmother (given that she isn’t a research scientist!).”

—Sonya M., fourth-year undergraduate, Northern Illinois University

What to look for

The info should acknowledge when research is incomplete or conflicting. “Sometimes, caveats are what make a claim truly applicable or not,” says Dr. Sonpal. Unbalanced articles are often trying to sell a product or belief.

Example

“The groundbreaking study found that adopting a confident posture can actually change your brain chemistry; however, similar studies have been unable to replicate those results so far.”

Red flag: Miracle cures and price tags

Miracle cures and so on are usually a sales pitch. Don’t fall for it. “Any article claiming a miracle cure that isn’t already a part of the evidence-based clinical guidelines set forth by a medical society should always be considered suspect,” says Dr. Sonpal. On that note, also look out for price tags. “Online health information should always be free—if an article is charging you for free information, it’s likely off,” Dr. Sonpal says.

Student voices

“I tend to stay away from websites or articles that are backed by certain diet movements, such as the vegan or paleo diet groups, because they tend to be biased towards that lifestyle and only present data to glorify them. This skewing of data and misrepresentation of results is misleading.”

—Lucas J., second-year undergraduate, Marian University, Indiana

“Accurate science usually doesn’t come packaged with a clickbait headline like ‘You won’t believe…’ or ’18 simple tricks that will surprise you.’”

—Elliece R., third-year undergraduate, University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

What to look for

Ideally, you want the content to be based on a meta-analysis or systematic review. These analyze data from many studies on the same topic. Meta-analyses are much more comprehensive and broadly applicable than any individual study.

Example

“A meta-analysis of 37 studies conducted over the past five years concluded that practicing mindfulness and meditation does in fact help reduce depression.”

Red flag: Few sources

Reliable health information is based on large, broadly applicable bodies of research. If the majority of the sources are the work of the same researcher or only apply to one very specific group (such as elite runners or grandmas in rural areas), tread carefully.

Student voice

“I like seeing statistics and reviews. I also research many different articles/reports and compare their information to see what sorts of things overlap.”

—Joree S., fourth-year undergraduate, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

What to look for

If it isn’t based on a meta-analysis or accredited review, the health content should at least be based on a peer-reviewed study done by researchers affiliated with universities or other respected institutions, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Example

“According to a joint research effort between Harvard and Johns Hopkins, regular aerobic exercise promotes longevity.”

Red flag: Biased funding source

Be wary of research sponsored by an organization that has an interest in the outcome (e.g., a study on soda and obesity sponsored by the soft drinks industry).

There should be no obvious conflicts of interest involving the author(s) or the organization(s) that sponsored the research. Additionally, the content shouldn’t assume that correlation equals causation. For example, researchers may find that people who do trampoline workouts have more joint problems. But that doesn’t mean trampolines cause joint problems—those jumpers might also be marathon runners.

What to look for

All or most of the content has been created within the past five years. “Many times, the medical community has been wrong or has advanced so much that old treatments are almost considered barbaric and archaic,” says Dr. Sonpal.

Example

“Scientists have been studying the benefits of exercise on depression since the 1970s, but a 2017 study that explored running as a treatment for depression made the case even more compelling.”

Red flag: Old sources

Some websites cite older information. This is OK if it’s a reputable source, like a university medical school, and it’s referencing a landmark finding, such as “smoking causes cancer.” Make sure the older research is paired with recent studies that expand upon or refine it. “If old studies are the only ones cited, that’s concerning, but if it’s a mix, that’s usually fine,” says Dr. Sonpal.

Student voice

“Trustworthy sites will work to keep the data as up to date as possible.”

—Rebekah S., sixth-year undergraduate, Rowan University, New Jersey

What to look for

Ideally, the research cited will have involved a large number of human participants. If the findings were only based on a dozen mice, the information can’t be applied to humans yet. “Animal studies should always be considered the beta version of clinical information—they’re the step before human studies,” says Dr. Sonpal.

Example

“To test the effects of sleep deprivation on school performance, researchers recruited 500 high school and college students and had them keep sleep journals for two months.”

Red flag: Cites studies using animals (especially small sample sizes)

“What happens in a rat won’t necessarily happen in us, especially if it was just one rat—we need to see it happen in larger studies,” says Dr. Sonpal.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Information on diseases, healthy living, travel health, and emergency preparedness from the US government

- Contains a wealth of data on different health conditions and topics such as occupational health and global health

- Vital Signs monthly report highlights recent studies and advances in public health

- Contains official government recommendations and warnings on everything from tattoos to tuberculosis

Cochrane Collaboration

- An independent network of researchers, professionals, patients, caregivers, and other people interested in health

- Summarizes the latest research to help you make the best health choices

Mayo Clinic

- Consistently rated one of the best hospital systems in the US

- Information on diseases, symptoms, treatments, procedures, and medications

- Symptom checker feature

Medline Plus

- From the US National Library of Medicine

- Information on various health topics, medications, and supplements

- Videos on topics such as surgery and anatomy, as well as interactive tutorials

- Games, quizzes, and calculators (for BMI, breast cancer risk, etc.)

Patients Like Me

- Online, disease-specific communities where over 600,000 members share stories and advice on over 2,800 conditions

- Free place to discuss symptoms and treatment options and ask experts questions

- Sells anonymous health data to companies and nonprofits developing health care products to help them understand the real-world experience of disease and treatment

PubMed

- Collection of over 24 million medical- and health-related studies from the National Library of Medicine, life science journals, and online books

- You can search by topic, type of study, publication date, and free full-text availability

CampusWell

- Evidence-based content on a variety of health topics

- Reviewed by health and wellness experts

- Tailored to your school

*Name changed

Why Dr. Google doesn’t work: Vox

A rough guide to spotting bad science (infographic): Compound Interest

Evaluating health information: US National Library of Medicine

Are popular nutrition and health sources reliable? [pdf]: North Dakota State University

10 questions to ask about scientific studies: Greater Good Science Center/Berkeley University

Article sources

Niket Sonpal, MD, associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency at Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in New York.

American Heart Association. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/

Belluz, J. (2014, December 10). Why so many health articles are junk. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2014/12/10/7372921/health-journalism-science

Belluz, J., & Hoffman, S. (2015, March 11). Stop Googling your health questions: Use these sites instead. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2014/9/8/6005999/why-you-should-never-use-dr-google-to-search-for-health-information

Caufield-Noll, C. (2012). Finding reliable health information on the internet: Overview of medlineplus.gov. [Slideshow]. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/JHBMC_CHL/medlineplusoverview?next_slideshow=1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov

Cleveland Clinic. (2014). [Website]. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/healthy_living

Cochrane Library. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.cochranelibrary.org/

EurekAlert. (2014). Educated consumers more likely to use potentially unreliable online healthcare information. Retrieved from https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-08/hfae-ecm082714.php

Flaherty, J. (2014). Spotting bogus dietary advice. Tufts Magazine. Retrieved from

https://www.tufts.edu/alumni/magazine/fall2014/discover/dietary_advice.html

Health on the Net Foundation. (2014). About HONcode. [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html

Mayo Clinic. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org

McCoy, T. (2014, December 19). Half of Dr. Oz’s medical advice is baseless or wrong, study says. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/12/19half-of-dr-ozs-medical-advice-is-baseless-or-wrong-study-says/

Medline Plus. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/

National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov

National Cancer Institute. (2012). Evaluating sources of health information. [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/health-info-online

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (2013). Finding and evaluating online resources on complementary health approaches. Retrieved from https://nccam.nih.gov/health/webresources

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.nih.gov

National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Evaluating internet health information. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/webeval/webeval_start.html

National Network of Libraries of Medicine. (2014). Evaluating health websites. Retrieved from https://nnlm.gov/outreach/consumer/evalsite.html

NHS Choices. (n.d.). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/

Patients Like Me. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.patientslikeme.com/

PubMed. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

Scholarly Open Access. (2015). [Website]. Retrieved from https://scholarlyoa.com/publishers/

Science-Based Medicine. (2013). [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org

Spurious Correlations. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.tylervigen.com/

University of Connecticut Health Center. (n.d.). Evaluating websites for consumer health information. Retrieved from https://library.uchc.edu/departm/hnet/rbevalwebsite.html

US Food and Drug Administration. (2013). How to evaluate health information on the internet. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/BuyingMedicinesOvertheInternet/ucm202863.htm